I always feel ambivalent about visiting

the sites of murders, death houses, scenes of long ago violent crimes. Partly it’s because of my inherent squeamishness. If there actually is some remaining malevolent

aura there, I’d rather not be around it.

And just as important, I don’t want to revel in and be entertained by the deaths of others, nor

to make light of pain, whether that of victims or survivors.

Yet I know one can protest too much about

these things. There’s no denying the frisson that comes with walking through,

say, Dealey Plaza in Dallas, or for that matter past the Bloody Tower in

London. I think the frisson is

imaginative rather than supernatural, but nonetheless real for that. One way or another a kind of shamanism is

involved, raising the spirits of the dead, but equally a kind of dubious

tourism is involved too

I don’t feel a whole let less ambivalent,

though in a different way, about visiting the homes where my “heroes” once

lived, even if I seem to have done plenty of it. In recent years I’ve found myself visiting JG

Ballard’s house in Shepperton, HG Wells’s in Woking, Raymond Chandler’s many

Los Angeles homes.

Of course when I say “visiting” I simply mean

that I walked down the street and stood around outside the building. I don’t go in for knocking on doors to interview

the current inhabitants, although I know some who do. My friend Anthony Miller, aka the Dark Sage of Sawtelle, recounts disturbing the tenants of Thomas Pynchon’s old apartment in

Manhattan Beach, and found the occupant, a surferish dude, amazingly hospitable. He invited him and let him look around. A Swiss film crew had been there not long

before, the one that made Thomas

Pynchon: A Journey Into the Mind of P.

The objection here is not that it’s

intrusive, but rather that it’s no big deal.

These are homes much like any other.

Everybody lives somewhere, lives don’t vary nearly as much as some

people like to think, and houses and appartments are not always totally fascinating. And in my experience there’s seldom any kind

of lingering aura, even if there may occasionally be a plaque.

Having said all that, and with all my

reservations, when I recently connected a couple of dots of information than

had been floating in my head for a while, and realized that the childhood home

of Don Van Vliet, aka Captain Beefheart, was in the same street where the

Manson murders of Leno and Rosemary LaBianco took place, well, you couldn’t

call yourself a psychogeographer if you didn’t take a walk down that street,

could you?

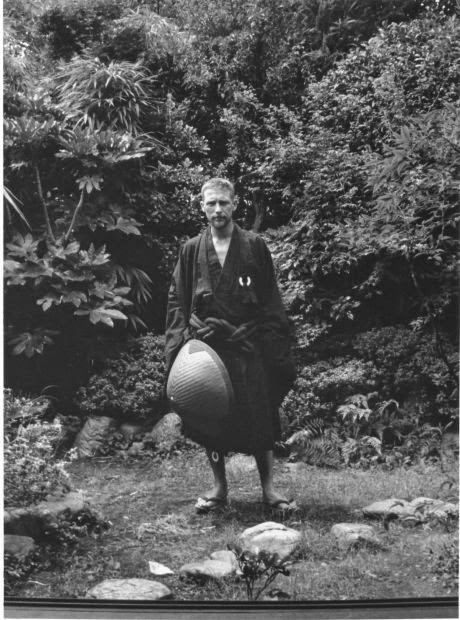

Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band were

really the first act that completely excited me in my difficult but dull

youth. They seemed subversive, poetic,

avant-garde, extremely cool – all the things I wanted to be. These days it seems to me that there were times

when Beefheart put rather too much effort into buffing his image as the

unschooled, sui generis genius born out of nothing, but I’ve had a few decades

to think about that. At the time the freaky

image was part of the attraction, and no doubt in some sense necessary for the

grand project.

Of course we also tended to think he was

some crazy guy straight out of the Mojave desert: we knew that he came from

Lancaster where he was best friends, later less so, with Frank Zappa. But before he was a desert rat he lived in

Los Angeles, at 3467 Waverly Drive, in the northeast corner of Los Feliz, a thoroughly

pleasant suburban enclave right below Griffith Park; a great place to bring up

kids then and now, you might think.

We also know that while he was at that

address he was schooled, at least to the extent of attending art classes at the

Griffith Park Zoo, where he was taught by a Portuguese artist named Agostinho Rodrigues. When he was

10 years old Little Don Vliet (he wasn’t even van Vliet at that time, much less

the Captain) won first prize in a 1951 sculpture competition run by the parks

and recreation department, and made it into the local paper with his model of a

polar bear. The contest was monthly, and

I don’t know how big the class it was, so winning it may not have been the

greatest honor, though his polar bear looks just fine.

There are a few pictures of the lad from

this period but I’ve never seen any of the family’s house, so I don’t know if

the current 3467 Waverly Drive looks anything like the way it did back in

1951. As far as that goes, I don’t know whether

Don’s parents had the whole house or just part of it. I’d assume the latter. In the current configuration 3467 is the right

half of the house, 3469 is the left half, and I think there are more than two dwellings

in there. When you peer round the side

it looks as though the building’s been extended to make a small apartment block,

though I’d guess the changes have been made post-1951.

Waverley Drive is a long street but the young

Don surely walked its length, in which case he’d have gone right past the LaBianca

house. At that time it would have been

owned by the previous LaBianca generation, Antonio, who founded Gateway Markets and the State Wholesale

Grocery Company. It wasn’t till 1968

that the son Leon, who by then was running the family business, bought the house from his mother and moved in

with Rosemary his second wife.

Photographs of the couple suggest they weren’t

much influenced by alternative culture, but Lord knows there were some

divergent energies abroad in Los Angeles at the time. Even in this quiet suburban enclave, the LaBiancas’

neighbor, one Harold True, had thrown an “LSD party”, and some of the Manson

family attended. The day after they’d

committed the Tate murders up on Cielo Drive, Manson instructed his followers to

kill again. They might easily have

selected a different house and different victims, and if things had played out

just a little differently the LaBiancas wouldn’t even have been home. They they’d been to pick up Rosemary’s

daughter Suzanne from Lake Isabella and had thought of staying there overnight

but decided to come back late Saturday night rather than the following morning.

Manson had found the Tate killings needlessly

chaotic, and to show his followers how it was done, he went into the house and

tied up the LaBiancas with the minimum of fuss, so that the killings could be

done in a nice orderly fashion. I’ve

done my best not to become a Manson obsessive, but if you need a full account

of the events, I reckon Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter

Skelter is still the best.

Photographs from the time show the La

Bianca house to have been remarkably accessible and vulnerable – a long straight

driveway, no gates, the house visible and inviting at the top of the hill, yet a

fair way from the street.

Some things are noticeably different at

the house these days; the street number’s been changed for one thing, though

that’s hardly bought them much privacy.

There’s now a gate across the entrance to the property, and you can see

that a large separate garage with a second curving driveway has been built

between the house and the street, at the very least providing protection from

prying eyes, though not inevitably from Google.

It still looks like a very nice house in a

very nice neighborhood. Would I

personally want to live in it, given its history? I suppose not, but if there price was right;

everything’s negotiable.

Charles Manson famously said to an interviewer:

My eyes are cameras. My mind is

tuned to more television channels than exist in your world. And it suffers no

censorship. Through it, I have a world and the universe as my own. So...know

that only a body is in prison. At my will, I walk your streets and am right out

there among you.

Captain Beefheart once sang:

my

baby walked just like she did

walking

on hard-boiled eggs with a --

there's

a --

she

can steal them

-

oh, I

ain't blue no more, I said

lord,

Words

to live by.