The other night I watched again (in a

half-hearted way) the movie of Misery. As many will know by now, James Caan plays

the writer; Kathy Bates plays his deranged greatest fan, and she works all kind

of mayhem on his legs, which were in any case broken in a car crash. She has her reasons.

Well it all turns out for the best, except

that the writer is left with a limp and has to use a walking stick when he goes

to meet his agent, played far more convincingly than you might expect by Lauren

Bacall, who is not most people’s idea of a literary dame. Caan is less convincing I think because in

general he (or maybe his persona) looks like a man who’s never actually read a

book, much less written one.

But the limp

is convincing enough, which isn’t always the case with actors. John Mahoney, who used to play Frasier’s

dad, is a fine actor but I always thought he had least convincing screen limp I

ever saw. He just seemed to do a few shuffling

steps while moving his cane, never actually using it for support.

On his website he fielded questions from

fans:

Kathy Smith asks: "Do you ever forget

to walk with a limp on the set of Frasier? Or do you find that when you stop

filming you still do it?"

John Mahoney: "Every once in a while

I do, sometimes I forget to use my cane, especially if you are doing a scene

and sitting down. Sometimes I jump up and walk away, the audience loves it,

they love screw ups."

How we laughed.

I know that Martin Crane is supposed to be a

former cop who got shot in the line of duty, and the interwebs tell us that he

got shot in his left leg, but from watching the show I’d never worked out which

leg was affected.

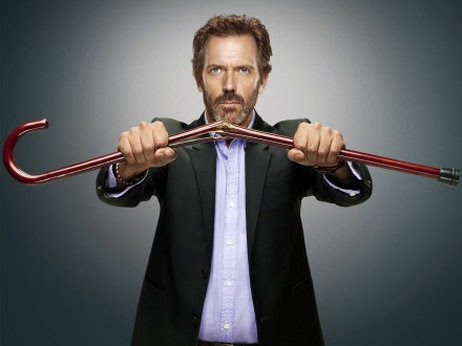

I was always more convinced by Hugh Laurie

playing Gregory House, though I know not everyone was, and the convincingness of his limp was apparently in

some danger of becoming all too authentic. A headline

in the Daily Mail a few years back read, “The limping Dr

House has wrecked my knees, says Laurie.”

This was an exaggeration, of course.

The article quoted Laurie as saying “The show might last through to

series seven, eight or nine but I don’t know if I will because I’m starting to

lose my knees. It’s a lot of hip work. There are things going badly wrong. I

need to do yoga."

Somehow Hugh Laurie always struck me as the kind of man who might do

yoga anyway.

At least in Midnight Cowboy,

Dustin Hoffman made his limp convincing by making it “real.” He put a stone in his shoe that meant he couldn’t

help limping. It seems like the perfect

solution, and one that other actors might like to try.

Or, like Hopalong Cassidy, they could solve the whole problem by riding

a horse.