A few days before the 4th of July 1932 a fifteen-year-old boy named

Louis Thomas Harden was walking along beside the railroad tracks near Hurley,

Missouri. The local mill pond had recently

flooded, and pieces of inscrutable debris were left beside the tracks when the

water receded.

Louis was a tinkerer, the kind of kid who made wooden models and built

projects out of Popular Mechanics magazine.

So when he found an especially intriguing piece of debris there where he

was walking, he picked it up and took it home with him. The object may have have looked something

like this:

On July 4th itself he examined his new find more closely. It proved to be a detonation cap left behind by a construction crew some distance away, and transported trackside by the flood. As Louis looked more closely at the object it exploded in his face, and despite some desperate and painful surgery he was left permanently blind.

In due course Louis Thomas Hardin

(1916–1999) became Moondog; an all-American original, a composer, musician, and

poet, who between the late 40s and the early 1970s could be seen in various

locations around Manhattan. At one point

he was a fixture in Times Square, but more often he could be found on 6th

Avenue between 52nd and 55th Street. He

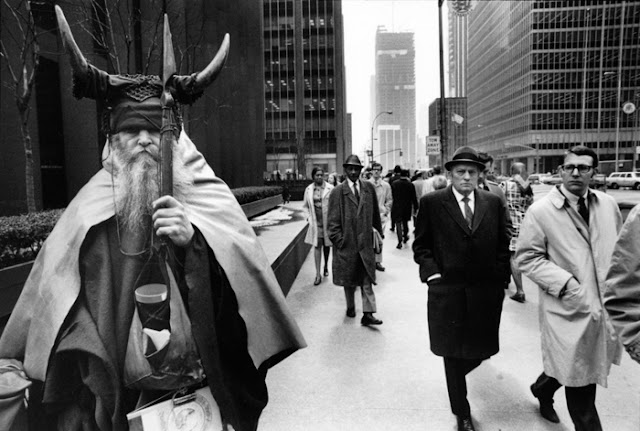

looked like this:

Sometimes he

played music, just like any busker, sometimes he tried to sell merch, and other

times he just stood there looking like a Viking. I’m sure he was photographed many thousands

of times, by gawking tourists as well as by serious photographers. The classic image shows him as the still

point, as the other walkers of New York swirl around him.

I’m always slightly surprised by how many blind people there are walking

the streets of Manhattan, especially when you consider how many sighted people

claim to be terrified at the prospect.

I’m sure Moondog had friends and helpers but he obviously

did get around the streets under his own steam. Philip Glass, in his essay “Remembering

Moondog” (which is the preface to Robert Scotto’s authorized biography Moondog, The Viking of 6th Avenue) writes, “he was

so confident in his walk you wouldn’t think he was blind. I wondered how, as a blind man, he managed to

cross the street without an instant of hesitation until he showed me how he listened

to the traffic lights; I had never heard them before in this way.”